They continually sprout from a volcanic hotspot, over millions of years move with the tectonic plates and the entire time develop new niches for some of the most spectacular species of animals and plants that continue to evolve in front of our eyes. Their chronosequence, the slow development of forests over time, can be effectively teach us a lot about soil formation, how the water moves across a altitudinal gradient and how these natural processes are impacted by anthropogenic interference. In a small scale, they can help us understand processes that could affect fresh water production in the whole of the tropics. Galápagos is unique and special without a doubt.

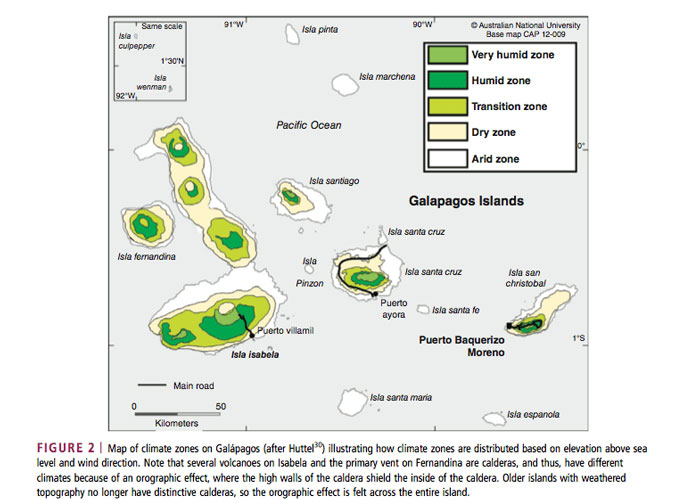

The volcanic hotspot of the Galápagos islands is located to the west of the archipelago, where the island of Fernandina is currently sits on. They all have the same bedrock foundation but the chronosequence of each island ranges from older to newer depending on when they formed. This can tell us a lot about the geological historical patterns and structure of soil formation and rooting. Larger islands have a distinct altitudinal gradient that range from very arid to very humid. This generates a range of microclimates, as well as different soil types and densities all of which have an effect on water movement across the gradient.

Research carried out in collaboration with the GSC by Percy et al. (2010) describe how “The difference in the soil water content across elevations on Galápagos not only has implications for agricultural practices… but also provides an excellent opportunity for an analogous site in the tropics of spatially intensive soil moisture observations”. The goal is to understand things like underground aquifers, formation of soil and soil erosion, how precipitation levels and fog determine the type of soil in relation to altitude. But also to understand what the effects of larger climatic events like ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) and ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone) have on the water cycle. These, as models, can help us understand better how to best preserve fresh water sources for in the Galápagos but applicable worldwide.

Fog is a very important component of high elevation ecosystems in the Galápagos. It promotes rain in the intermediate zones, where most of the agriculture takes place. Land use has changed over the years, many farms have been abandoned and invasive plants are taking over these cleared spaces. Also, the increase in tourism means more infrastructure and a greater demand for water and goods. “These disturbances all have direct and indirect impacts on hydrological processes and the partitioning of precipitation into evapotranspiration, runoff, and groundwater recharge” affirm the authors. If the fog goes, so do the best lands for food provision. Changing soil use to the extent where the water cycle is permanently disturbed could have disastrous consequences. Luckily for us (for the beautiful tropics and our future generations), we are gaining better understanding of this everyday.

But, conclusive decisions need to be turned into effective action fast. As climate change begins to feel more real everyday, we must ensure our fresh water sources are well managed. It is now in all of us to make sure we take care of every drop we use.

Reference

Percy, M.S., Schmitt, S.R., Riveros-Iregui, D.A. & Mirus, B.B. 2016. The Galápagos archipelago: a natural laboratory to examine sharp hydroclimatic, geologic and anthropogenic gradients. WIREs Water. 3:587–600. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1145.